A Crucial Moment in IPF: What Boehringer Got Right, Why Roche Walked, and What’s Next

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) has long been one of biotech’s most unforgiving proving grounds. Despite decades of research, billions of dollars poured into drug development, and a clear unmet medical need, IPF has remained a market with high hopes and even higher failure rates. Drug developers enter the space convinced they have cracked the code, only to watch their Phase 3 trials implode in spectacular fashion. If cancer drug development is a game of strategy and iteration, IPF is more like a slot machine that only pays out once every 15 years.

For more than a decade, only two drugs—Esbriet (pirfenidone) and Ofev (nintedanib)—have been approved to treat IPF. While these therapies have been effective in slowing disease progression, they do not halt or reverse fibrosis, and their side effect profiles make them difficult for many patients to tolerate. Yet, despite the limited options and an obvious commercial opportunity, every major attempt to bring a new drug to market has resulted in disappointment.

Yet, in just the past few weeks, three major events have reshaped the IPF competitive landscape:

Boehringer Ingelheim’s nerandomilast succeeded in a second pivotal trial, this time in progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF), after already demonstrating positive Phase 3 data in IPF.

Pliant Therapeutics’ bexotegrast paused its Phase 2b/3 trial in IPF, calling into question whether this once promising asset will be added to the long list of late-stage IPF drug failures.

Roche sold off its InterMune business (which included Esbriet) to Legacy Pharma, signaling a strategic exit from the IPF space.

These events highlight both the opportunities and challenges in IPF drug development. While BI has now emerged as the dominant player, Roche’s exit raises questions about the long-term commercial prospects of the space. Meanwhile, Pliant’s setback is yet another reminder that IPF drug development is an unforgiving landscape where pretty much every company has stumbled.

Why Is IPF Such a Drug Development Graveyard?

The history of IPF drug development reads like a long list of companies that almost made it. For years, IPF has been a target that attracts well-funded biotechs and big pharma players, only for them to run into the same brick wall in late-stage development. Over the past five years alone, multiple high-profile drugs have failed in Phase 3 trials. FibroGen’s pamrevlumab, a CTGF inhibitor, collapsed after early signs of efficacy failed to translate into meaningful clinical benefit. Galapagos’ GLPG1690, an autotaxin inhibitor, showed promise in mid-stage trials but ultimately fell apart in Phase 3, a pattern that has repeated itself in the space with almost eerie consistency. Roche’s own attempt to expand beyond Esbriet with zinpentraxin alfa (PRM-151, recombinant pentraxin-2) also failed in late-stage trials. And now, Pliant’s bexotegrast, an integrin inhibitor, could be on the verge of joining the growing list of promising drugs that never made it past Phase 3.

The obvious question is: why? Unlike some other challenging therapeutic areas, IPF has a clear unmet need, established clinical endpoints, and a well-characterized disease progression. In theory, this should make it easier—not harder—to develop new drugs. But as history has shown, IPF has a way of confounding even the most promising mechanisms.

One major challenge is the unpredictable nature of disease progression. IPF is highly variable from patient to patient. Some patients experience rapid lung function decline, while others remain stable for extended periods. This variability makes it extremely difficult for clinical trials to show consistent treatment effects across a study population.

Many failed trials have been undone by placebo arms that performed better than expected, shrinking the apparent benefit of the investigational therapy and making it impossible to achieve statistical significance. Unlike in oncology, where tumor progression is somewhat clear-cut, IPF trials use FVC (Forced Vital Capacity) decline as the primary endpoint. If the placebo group declines slower than expected, the drug’s effect size looks smaller than anticipated.

Another obstacle is the biological complexity of IPF itself. Unlike diseases where a single dominant pathway drives pathology, IPF involves a complex interplay of epithelial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, fibroblast overactivation, and collagen deposition. Many past drug candidates have targeted only one of these pathways, which may explain why they have consistently fallen short in Phase 3. Fibrosis alone is not the problem—it is fibrosis in the context of chronic inflammation, aberrant wound healing, and immune dysregulation that makes IPF so difficult to treat.

Toxicity has also been a recurring roadblock. Fibrosis is a necessary biological process for wound healing and targeting it too aggressively can lead to off-target effects that create new risks for patients. Some investigational drugs that looked promising in preclinical models turned out to be too toxic for long-term use, forcing companies to abandon them even after encouraging early data.

Boehringer Ingelheim Takes the Lead in the IPF Race—For Now

Amidst this sea of failures, Boehringer Ingelheim may be on the verge of doing what no other company has been able to do. Nerandomilast, a PDE4B inhibitor, has now delivered two successful Phase 3 trials—one in IPF and another in progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF). This makes it the first new therapy in over a decade to show a clear, statistically significant benefit in slowing lung function decline.

What makes nerandomilast different from the long list of failed candidates that came before it? The most important factor is its mechanism of action. Unlike past drugs that have primarily targeted fibrosis or inflammation alone, PDE4B inhibition affects both. This dual approach may be the key to why nerandomilast has succeeded where others have failed. Additionally, its tolerability profile appears to be superior to Ofev and Esbriet, which could make it a more attractive treatment, either as a monotherapy or in combination with OFEV or ESBRIET. If the regulatory path is smooth, nerandomilast is well-positioned to become the new standard of care in IPF.

Roche’s Exit: A Strategic Move or Capitulation?

While Boehringer Ingelheim was delivering a long-awaited success story, Roche was moving in the opposite direction. In a move that caught many industry observers off guard, Roche sold off its Esbriet business to Legacy Pharma, signaling a strategic retreat from IPF. At first glance, this seems like an odd decision—after all, Roche paid $8.3 billion to acquire InterMune for Esbriet back in 2014. But a closer look suggests this was a calculated move rather than an impulsive exit.

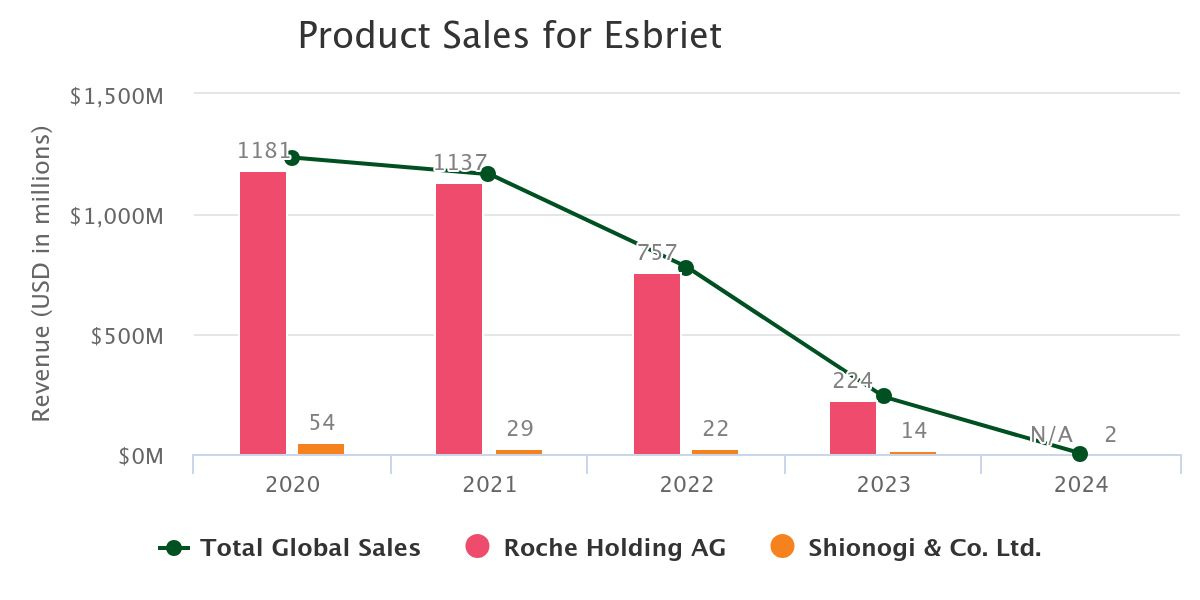

The biggest factor behind Roche’s decision was likely Esbriet’s declining commercial outlook. With generic competition entering the market in 2022, Esbriet’s revenue potential was diminishing relative to BI’s OFEV. ESBRIET sales reached a peak of $1.2B in 2020 but steadily began declining and eventually cratered upon generic entry. Meanwhile, OFEV has outpaced ESBRIET and is a ~$3B product

Additionally, Roche lacked a strong successor drug to replace Esbriet. PRM-151 failed in clinical trials, leaving Vixarelimab, an anti-OSMR antibody currently in Phase 2, as Roche’s only remaining IPF candidate. If Roche had high confidence in Vixarelimab, it would have made sense to keep Esbriet as a commercial bridge until the next-generation therapy was ready. But selling Esbriet suggests Roche saw limited potential in Vixarelimab and chose to cut its losses rather than continue investing in a shrinking market. Overall, it feels like Roche has deprioritized IPF altogether.

The IPF Market Just Got Interesting

With Roche stepping aside and Boehringer Ingelheim surging ahead, the IPF market has entered a new era. For years, IPF drug development was defined by high hopes followed by disappointment, but now, nerandomilast has broken the cycle. The next two years will determine whether this is the beginning of a new wave of innovation in IPF or if the field remains a high-risk, low-reward battleground.

Boehringer Ingelheim now has the clear lead, but competition could emerge if companies begin exploring combination strategies or novel mechanisms beyond fibrosis and inflammation alone. For now, though, IPF belongs to Boehringer—and everyone else will have to play catch-up.